Essay

When Ordinary Becomes Beautiful

Yasmin Bouhafs

Wen Fang graduated in 1996 with a degree in graphic design and began working as a web designer. For six years, she excelled in this field but a strong passion for photography drove her to France to study photography at the Louis Lumière School in 2003. "The most important thing I learned during my two years of study in France was to have an open mind," Fang recalls. "My experiences in France have made it easier for me to understand others and their differences." Although considering photography as her profession then, Wen Fang nonetheless did not stay interested in traditional photography for long. "You print the photographs on paper, frame them, and hang them on the wall. This is very limiting of what a photo can be; it is more like a grave for the photograph," says Wen Fang. She therefore has tried new approaches to make photography and incorporate into her works the material elements of daily life such as brick, wood, leaves, water, and even air.

One result of Wen Fang's unconventional approach to photography is her Golden Brick series, in which she managed to print photos onto the surface of cement bricks and arranged them into various installations to express her critical commentaries of the downsides of China's rapid urban transformation. With this series, she started to be known by the Chinese contemporary art world around 2008 and some of her works entered into the collection of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Arts Foundation. In 2009, Wen Fang was invited by Dior, as one of the 22 internationally renowned Chinese artists, to celebrate the brand's 60th anniversary and participate in the exhibition "Dior & Chinese Artists," which was an attempt to cross the established boundaries between high art and crafts and between art and commerce.

Wen Fang had several solo exhibitions related with the Golden Brick. Among them, "Foundations," showcased in 2008, was the best received and it opened the doors of success to her. It is an installation consisted of 300 faces of migrant workers printed on cement bricks. This was her way to pay tribute to the mingong (migrant workers) who helped build major cities such as Beijing. Following this success, Wen Fang continued to make art based on the lives of disenfranchised social groups. She dedicated a photographic installation to children living in orphanages in southwest China that were supported by Children of Madaifu, a French NGO, and returned the profits generated from selling the work to the organization. A short time later, she heard about the hardship of women embroiderers living in Ningxia, a poor and arid region of China, through another French NGO that was working to get them out of poverty. Wen Fang initiated collaborative art project that invited these women to work with her in making contemporary art works. In 2010, she organized the exhibition "Textile Dreams," which marked the encounter between the traditional embroidery of these women and the creativity of her as a contemporary artist. Wen Fang's perception about art has continued to evolve and in recent years she no longer feels obliged to put her art at the service of NGOs or fit into a mold by dealing with the social problems in China. As a result, she feels freer to experiment and has taken up video, performance, and land art, along with photography, as her media of art making.

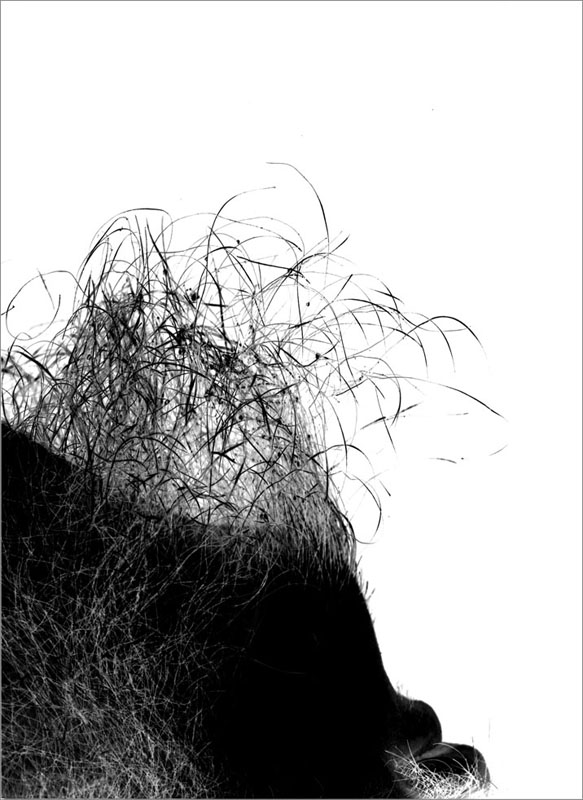

No matter what media Wen Fang has taken upon, however, her art always expresses an interest in discovering significance in grassroots materials and lives of ordinary people. In addition, she also likes to push the boundaries and test new possibilities of art making. Both appear early on in her artistic career, even before she started engaging in the unconventional photographic practice, and her The Ideal World series is a good case in point. Starting in 2005 with final touches in 2019, she took close-up shots of nude bodies from her friends, old and young, male and female, and transformed the ordinary body parts into meaningful and unexpected beautiful imageries.

The series plays with two different traditions of art, the West and the East. Wen Fang believes that the art she learned in France has developed out of a deeply rooted Western representational art legacy centering around traditional sculpture and oil painting, which emphasizes three dimensionalities. On the other hand, calligraphy and ink painting, which she studied since little, emphasize two dimensionalities and abstraction. For her, they represent the essence of Eastern traditional art. The black and white photographic series The Ideal World came from her experimentation with the possibility of merging the two artistic traditions, abstract art and representational art. When making this series, she said she was particularly inspired by the bold and daring abstract ink paintings from the famous Chinese artist Zhu Da (1626-1705). Using human body as the ground, she manipulated with the elements of black and white and light and shadow as a way to cross the borders between abstract art and representational art.

The five pieces of The Ideal World included in the exhibition give a good overview of Wen Fang's experiment with photography as a medium to bridge the two artistic traditions. Respectively portraying belly, chin, eye, limbs, and lips (The Ideal World-9, -12, -26, 27, 28), She reversed the black and white relations of body parts in the photos she took and they can look like anything depending on the viewers' imaginations. The strong contrast between the white and black or the subtle interplay of them reminds well of the art of Chinese ink painting. She pays attention to the harmony of the composition and the balance of the masses. Here, she creates a new way of showing the body outside the academic tradition of nude art. Because viewers sometimes do not recognize what part of the body is in the image, they can be drawn into its shape, scale, texture, lines and curves. Upon closer examination, they might recognize the specific body part or they might never and simply see the image as a portrayal of landscape.

The Ideal World-9

The series also touches on the subject of beauty embodied in human body. Wen Fang adopts a positive attitude towards human body regardless of its conditions and even embraces the undesirable cause of nature as it works on the human body. The title The Ideal World speaks to her very attitude of seeking beauty in ordinary and her ability to transform commonplace phenomena into insignificant forms.

The Ideal World-12

Social networks are omnipresent in our daily lives. Thanks to these technological means, we are exposed to an infinite number of images that reinforce the standards surrounding the idealistic human body, especially the slender and athletic bodies of women. These ideals are then internalized by women, creating enormous pressure in their lives, such as physical training and nutrition. These standards, which can be unrealistic and therefore difficult to achieve, also cause women to feel emotionally uneasy about their body image. In addition, women tend to publish selfies more often and use more technological means to modify their selfies, thus reinforcing unrealistic body standards. Finally, the more women compare their physical appearance with that of celebrities publicized in mass media, the less satisfied they tend to be and the more concerned they become. These pair comparisons often introduce body shame and a perceived need to lose weight. In this context, the vast majority of women, and an increasing number of men, are dissatisfied with their own body image.

Wen Fang's The Ideal World is a total departure from the popular standards when it comes to bodies. It aims to capture and manifest beauty through shapes, wrinkles, folds, unevenness, roughness, and signs of aging that naturally take place and organically form in human bodies. Wen writes: "Through my camera, you discover the beauty in every face, in the mountains and vales [that appear on the body], in the seasons that go by. You belong to this nature; you are this nature." Apparently, her concept of beauty does not limit to those popularly accepted standards promoted in various social networks and mass media. Rather, with an artistic vision, she can find it everywhere.

The Scars of Urbanization

Jim Severtson and Maxine Lemuz

This is a representational piece of art. This is an abstract piece of art. This is a quick study for a detail of a painting. This is a finished painting representing a Claude Debussy Nocturne. This piece is heaven. C'est extraordinaire. It is (Extra)ordinary.

These words can be said for many pieces that constitute Wen Fang's Wall, a photographic series that she completed in 2006. Inspired by the decaying walls in Beijing's Forbidden City and the surrounding residential area, she took a large number of photos documenting interesting patterns and imageries appearing on these walls. Discussing the series, Wen Fang says: "After more than a decade taking photographs of dilapidated walls, the beauty in the abandoned always touches me. Since many people could not understand, I edited the photographs slightly so that you could see what I see." Instead of merely treating what appeared on the walls as beautiful and abstract images of natural causes, however, she perceives them to be the scars of Chinese urbanization. In response to Wen Fang's work, Chinese art critics Li Xianting states: "over the past twenty years, the frenetic urbanization that has taken place in China has transformed the destiny of the majority of Chinese people and destroyed much of both their culture and tradition." The series thus straddles the past and present and at the same time is a perceptive look at the massive expansion of the urban space in China.

Crumbly, decayed walls covered in vibrant red paint symbolize the values of Beijing's ancient culture. The aging of the walls can also be compared to our human skin and what happens to it after death. Our skin crumbles and the flesh dissolves, revealing our blood, vessels, and bones. Urbanization is the process of destroying the old buildings of a town and replacing them with new buildings to create a city-like environment; urbanization also brings problems with it, such as dislocation of the lower class, gentrification, and loss of culture.

Looking at any particular piece in the series, one may wonder: Is this wall still extant? Has it been demolished and in its place, some more efficient and well designed structure put up? Has the area in which it is located become gentrified as we say in the West, or do the demographics of the area now include the displaced and less fortunate citizens of China? Viewing her works can become an experience the viewer feels viscerally; its effects linger long after the viewing, and affect how we look at walls we encounter on a daily basis.

Wall-1 is the first photo Wen Fang took and it gives an indication of what is to come in the series that will follow. This image, in muted blue and beige with a prominent dark bottom edge, is evocative of a dragon which is apropos for a Chinese wall. The movement of the "serpent" is evident, from right to left, undulating, arching in the center of the image. The use of light and dark prevails throughout with the mood being mostly dark, ranging from the black at the bottom of the image to the middle ranges in the serpent; the white highlights are framing the underbelly on the monster and unifying the parts as a whole.

Wall-1

The overall feeling of the image is one of reflection rather than fear or dread. Symbolizing powers over the natural world, particularly the waters of earth, dragons can bring good luck to those who are worthy. Seeing an image within an abstract art piece is not uncommon, but sometimes it takes hard work and a lot of interpretation which not all can see. This is an exception, however, because the association is so obvious that even Westerners can easily see. The image has a painterly quality, as we would see in a Chinese painting, a landscape, or an allegorical painting.

The red in Wall-2 indicates the location of the wall: in the Forbidden City. The complex in central Beijing that currently houses the Palace Museum was the imperial palace for over 500 years, and the common populace of China was forbidden entrance. It, too, has seen decay, and the image gives a feeling of the murky past of that place, the self-contained areas, the separation between the emperor and common folks. Leaving that once powerful place behind, we can read interesting things out of the photo itself. The bright red resembles something that is being looked at under a microscope. Comparable to the composition of blood cells, the right side of the wall carries a scratchy texture one can get lost in. The contrast of color on the left side of the photo, make the biomorphic-like circles appear as clouds. The left side of the wall can be perceived as a rainstorm cloud over a mountainous terrain. The photo looks as if it was an intentional painting with a gradual scheme of dark to light across the work. Hues of gray and blue can be found throughout the layers of the exposed wall.

Wall-2

Wall 4 shares similar characteristics such as the cell like shapes appearing in high contrast of light to dark hues, but all these unfold in a color palette of blues, pinks and black. The texture consists of cracks and rugged marks, fragments of a decomposing wall. Amoeba like forms are floating around in the photo. The left side of the work is airier and lighter colored in contrast to the left side of the piece, which holds the darker hues and forms. This is an image both plain and wonderful. It's different from the colors of many of the other Wall works and presents as monochromatic. The contrast effects imply a three-dimensional subject matter to the image, as if we are suspended among very close and very distant nebulae beyond our galaxy. Like other pieces from this series, there is a great amount of organic material seen within the decaying wall.Knowing that we are looking at a crumbling wall, we feel a dystopian decay, but what beauty the decay presents!

Again, the tell-tale red in Wall-5 is indicating the original location of this wall. Differently from other images in the series, we don't have to imagine much of what is going on here since it is less abstract and thus easier to comprehend the content of the photograph. In the center we see a square consisting half of bricks and half of an old wall, which is surrounded by a vibrant red and decomposing wall. The red paint is cracked and towards the bottom we can make out the structure of the underlying bricks. This photo can be read as a pure and raw representation of the scars of the old city and what was left after the urbanization of China, "though the buildings were destroyed, it is impossible to erase the joy and suffering of those who have moved away and the cultural shifts that have punctuated history."

Wall-5

Different from most pieces in the series that are presented in landscape format, Wall-13 is a pair of vertical walls; there is no layering of images on top of one another and the monochromatic feeling goes a lot farther than other images. Of all the pieces, this perhaps is the most "elegant" in its portrayal of decay and the destructive results of urbanization.Two sections of wall in Wall-13 give a rich impression of decay. The natural phenomenon of the decaying wall becomes extraordinary in the style of Gustav Klimt, and the randomness of decay becomes a tapestry of golden richness in the pairing images with the intricacy of weave displayed throughout. Through Wen Fang's artistic vision, the urban decay has become the beauty which remembers the past; who knows how the current form was created and out of what materials from the past, but it is working real well as an interesting and satisfying portrayal of that beauty.

Wall-13

The color scheme in Wall-15 is saturated red and black contrasting for the attention of the viewer's eye. The other minor colors, spread across the image like as a painter would carefully scramble pigments into the canvas, create accents in blue, white, and pink. The overall visual impression is that of controlled execution of brushwork from an experienced hand. Yet we know all these are the accumulative result of wear and tear over the years via natural elements or incident human hands. One cannot help but wonder about its age and how many unintended scrapes of people and wagons the wall experienced in the past.

If Wall-15 appears to be done by a controlled hand, Wall-17 presents a rather free style as if it was resulted from diluted pigments poured or splashed onto each other. Colors in this photo create a focused theme with the red and blue, the violet and purple hues. As pigments flow and spread all over the surface, our eyes stretch in all directions as well. It is a manifestation of the continuous metamorphosis of substances as nature exercises its mighty and unpredictable power.

If all other pieces included in this exhibition tend to be intense and engaging, Wall 18 brings on a restive and calming feeling. The photo has a color scheme that is close in value with only two hues and the absence of wide value contrasts allows the mind to drift as if on a peaceful ocean. This is a break away from the intensity that we have experienced reading other pieces in the series, and maybe a temporary relief from the conflict between the relentless urbanization and the dismantled past which is the thesis of the series.

Throughout, Wen Fang found aesthetic and social significance within the abandoned ruins of Old Beijing. She captured their essence and helped them share their story. She expanded the size of the photos making them even more breathtaking and vivid. The effects of urbanization is real and this is only one example of how she makes a statement without saying one word.

MASKBOOK: A Call for Participation and Action

Yueming Wang

Urbanization has affected every aspect of Chinese society. As a fast-growing emerging economy, China is experiencing the impact of extreme urbanization as a consequence of the government's pro-urban developmental strategies in the past several decades. The rapid increase in urban population, as the countryside declined and rural residents migrated to cities in millions looking for better job opportunities, has led to the unrestricted expansion of cities. Consequently, the rising consumption and increased resource use have brought about many social, cultural, and environmental problems to urban residents. Among them, air pollution has emerged to be a major problem that shadows Chinese cities and threatens the health of urban residents. As a matter of fact, it was reported that hazardous smog has become the fourth-leading factor for premature death in cities in China.

Of course, in the age of global capitalism, which thrives on the relentless exploitation of natural resources and the promotion of mindless consumption, air pollution is not a man-made plague only limited to China. Worldwide, people are suffering from unpredicted consequences of environmental deterioration and air pollution has become common in cities across the globe. Maskbook was initiated as Wen Fang's artistic response to this global problem. As an artist, she seeks to accentuate the potential of art to address environmental problems, raise people's awareness, and get them involved into taking action. Maskbook was designed to be a collective public art project, to be participated and expanded by people all over the world. Instead of viewing it from a bystander's point of view, the work encourages hands-on participation and embraces every ordinary people's creativity and their understanding of climate change.

From a historical perspective, cities change all the time, and the public's demand for cities is continuously evolving. In the development of modern cities, the transnational exploitation of natural resources and the ruthless destruction of the environment have made cities increasingly unlivable. An urgent need facing urbanites worldwide in our contemporary times is to reclaim the livability of cities and public art has played an increasingly important role in this regard. Besides its well-acknowledged functions for aesthetic improvement and enhanced building design, it has been argued that public art can contribute to the resolution of a range of broader physical, environmental and economic problems. Public arts advocates argue that art is able to enhance civic identity and produce a number of positive social benefits. Maskbook is such a public art work that embodies a progressive aspect of the urban culture and civic ideals since it aims to address a prominent problem created by the modern city life.

At a meeting with Art of Change 21 in 2014, Wen Fang said: "In China, because we all wear anti-pollution masks, Facebook is China should be called Maskbook (mask book)!" Thus came the name for the project. In 2015, Maskbook project was officially launched by Wen Fang in association with Art of Change 21 on the occasion of COP21 in Paris. Wen Fang hopes to encourage individuals to do more than just making masks since she believes that we are all responsible for the climate change and we need to do our part. With Maskbook, every single anti-pollution mask is a symbol of pollution, a means of action, and a canvas for creation. It was meant to be an international, participatory, and artistic project that could help to raise public awareness on the connections between health, air pollution, and climate change. Since the launch of Maskbook, Wen Fang continues to play an important role in the project and has regularly held Maskbook workshops in different cities so as to get more people involved in thinking about climate change and participating in this global civic work through making their own masks.

The special thing about Maskbook is that common people, from all different nations, have contributed to this project. It promotes the idea that in order to solve the environmental problem, people all over the world need to focus on finding commonalities instead of differences among them. Nowadays many people are talking about environmental protection, but there are few people who put ecological protection into action. Wen Fang said, "As an artist, I have a responsibility to do something, instead of just waiting and complaining." She therefore hopes to inspire people into taking concrete actions. From this point of view, Maskbook is not only a representation of the environmental issues but also a stimulant for grassroots positive energy and a platform for social change.

Fundamentally, artists can raise the question and give it to people, make people using their methods to expose environmental problems and seek solutions. While these people can be ordinary persons, the determination to make change happen can transform them into pioneers. The small action they take has the potential to change the whole world for better when done collectively. Just as in Maskbook, Wen Fang believed that people can also make efforts to solve the smog problem, rather than just wearing masks and isolating from the outside world as an ostrich.

Maskbook, selective screenshots from the video, 2019, 1.45 minutes

Essays for Non Exhibited Works

Terra Cotta Migrant Laborers of People's Republic, 2008

consisted of 300 cement bricks, each 11.81 x 5.5 x 2.76 in. (30 x 14 x 7 cm.)

Wen Fang's photographic installation Terra Cotta Migrant Laborers of People's Republic is dedicated to migrant workers in China. Consisted of 300 portraits of migrant laborers that are printed on bricks made out of cement, it expresses Wen's critical commentary of China's urbanization and its impact on different social groups. She sees that because of the existence of the household registration system (hukou), people from the countryside and thus are registered as rural residents cannot enjoy social benefits provided to urban residents, despite that fact that a large number of them are working by Suzana Vartanyan

Facing the Sea, with Flowers Blossoming in Spring, 2009

installation, size variable

Wen Fang's installation piece,

entitled Facing the Sea, with Flowers

Blossoming in Spring, is dedicated to the victims of the 2008 Sichuan

earthquake. This installation art is built with bricks, broken structures,

blocks of cements and destroyed building materials covered in dust. There are

dishes, furniture, blankets and flags, objects that people normally would have

in their ordinary households. This is a representation of millions of houses

that were destroyed by the natural disaster.

Not only the physical building itself was destroyed but also the

household that was keeping the family together, where they lived, built their

life stories, and a place that was supposed to keep them from danger. It can

also has another interpretation, like the destruction of an old home in order

to build a more up-to-date urban structure. The work captures the feeling of

loss, sadness, and agony. Looking beyond the grievance on the floor, however,

there is a hopeful message from the title of a poem written by poet Hai Zi

explaining his ideal happiness. By using

Hai Zi's poem, Wen Fang is saying how important it is to look beyond sadness

and loss, and keep on overcoming these feelings to find peace and hope. by Marvin Merlos and Yunhee Lim

Rain, 2009

consisted of 300 steel knives, each 11.81 x 5.12 in. (30 x 13 cm.)

The power of art can change one person's view, or it can cause a national or even international movement to seek change. Nicholas Serota states, "Arts and cultural companies possess a significant purchasing power and can be instrumental in persuading suppliers to make ethical decisions and develop greener products and services." Wen Fang has created art that does not just raise awareness but forces us to face the truth that we are all in this predicament together. There is no escaping or hiding the apparent truth in the wake of how our unconscious choices as humans have brought about the destruction of mother earth.

Wen Fang's art piece titled Rain, a photographic installation consisting of 300 images of garbage printed on steel knives,addresses the problem of trash affecting China directly. She uses photography creatively by printing the photographs of trash that plague the urban streets of China on knives in an installation. These knives are then suspended by strings from the ceiling where gallery patrons can walk under them; this signifies the problem of waste metaphorically, as if it is raining from the sky uncontrollably on to the heads of the people of China. The knives not only signify the danger and destruction, but forces the viewer to see trash as an inherent problem that they themselves may have ignored when walking through the urban streets of China. Think about gallery patrons as they look up at the sharp tips dangling above their heads, one can only imagine the sense of unease if any of the knives were to come down when gravity beckons it. Wen Fang intentionally wanted her patrons to feel the same unease she did when she visited poor neighborhoods plagued by waste. by Francis Robateau

The Art for Craft's Sake

2009 - 2012

The Art for Craft's Sake (2009-2012) is a multiple year project centers on the idea of creating participatory art that would be beneficial to everyone involved. The project aims to lend contemporary art to support traditional crafts, a departure of the modernist tenet of "art for art's sake." It concerns Wen Fang collaborating with 15 craftswomen from an impoverished town in the Ningxia province and together they created artworks using traditional embroidery techniques to express the living conditions and aspirations of these women. Wen said of the women, "Even if these people were in purgatory, they would invariably reveal the light within their hearts. It is the light from heaven. I see that light from these women."[1] She therefore organized an exhibition entitled "Heaven" to display the works created by them and arranged a round trip for all of the women to attend the opening ceremony in Beijing. Many of these women had not ever been inside galleries despite being craft-makers, so this was a big experience for them. In addition, Wen contributed half of the proceeds back to the women to create a fund that would alleviate their financial difficulty. Garland was one of the first collaborative pieces created by Wen and the women. It told the story of their lives as housewives in a rural and impoverished area. It is a garland made up of embroidered insoles hand embroidered by the women. These women are skilled at what is often considered handy-crafts, and they typically create these insoles to go into the shoes of their loved ones - most often men who travel far into the city for work. Despite their seemingly insignificant function, they are thoughtfully and intricately made, becoming beautiful objects for everyday use. By bringing these women into her work, Wen strives to bring upfront the artistic skills possessed by these women and to create a condition in which all parties could benefit from the collaboration. Her intentions drive home the artist's value of being socially active and making a difference where she can. by Emma Macias

Broom and Mop, 2011

installation, size variable

Broom and Mop by Wen Fang is an art installation made in 2011 out of Fiberglass-reinforced plastics, human hair and hemp rope. When looking at this art piece the viewer sees cleaning tools but if taken a closer look, the handles resemble bones with human hair attached to one end. Wen Fang states "When I created this work, I was awaiting the birth of my first child. My friends asked me why at this time I created a work that was related to death. I think maybe it was because we can not know life until we know something about death." Indeed, everything comes to full circle here. Women give birth, take care of their offspring, grow old and eventually, they come to an end and pass away while their children continue the life cycle. "No matter whether our life is glorious or bleak, when we pass away from this world and go back to earth, hair and bone will be the last two things that remain in this world." After death and buried, almost everything of a human body will decay and disappear in time, except for its hair and bones, the only remains of what's left of that person. Having both these cleaning tools together instead of one of them standing alone, the work seems to give a sign of bondage. In everyday life, the pair are always associated together with the broom sweeps, moves, and collects particle while the mop absorbs certain liquid and removes stubborn dirt and grime. What they do resembles the cycle of life and death. Living life gives you the ability to grow and move around and collect information like that of a broom. Death is the end of a life so one absorbs, takes everything with them, and decays/dries up like that of a mop. Apparently, this installation piece could be seen as Wen Fang's contemplation of the cycle of life and was thus very personal to her, as she prepared for giving life to her first born. By Jeanette Benitez

Land Art and Me (2018)

selective pieces, 2018, installation, size variable

Wen Fang's collaborative work Land Art and Me (2018) is an attempt to develop intimate dialogues with nature and it speaks to Wen Fang's environmental consciousness and her desire to transform ordinary daily experience with art. This is a series of photographic images that document how natural settings, such as land, a rock, an old wall, a tree stump, can be slightly manipulated through harmless and lighthearted artistic endeavors to produce interesting and engaging visual effects. Created by Wen Fang and children from an orphanage that she supports, they used safe materials directly coming from nature, such as flowers, fruits, leaves, plants, rocks, and sticks to create aesthetically pleasing patterns and compositions. Photographs from the series show the processes and final products of the working of human minds and hands on natural objects in natural environment. For example, they moved small flowers to form a circle on a rock, used sticks to create words hanging down from a tree, or carve leaves into animal shapes or human figures. Overall, the series centers on nature, either with a human in it or showing the working of human hands. There is a prevailing sense of peacefulness and elegance throughout that encourages one to take a step back and appreciate the wonder of nature. By Genavieve Mather and Meiqin Wang